By Bhabesh Dutta, Govindaraj DevKumar, Brian Kvitko and Hemant Naikare

Organic onion production has grown substantially over the last two decades with the adoption of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program (NOP). Consumer demand for organic food is rapidly increasing. U.S. organic growers, both large and small, are benefiting from this trend.

Organic onion production faces several challenges; pest and weed pressure are the prominent ones. Recently, another looming challenge that appeared in onion production is the potential for produce contamination by foodborne pathogens. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the 2020 outbreak caused by onions contaminated by salmonella bacteria resulted in 1,127 illnesses and affected people in 48 states. While red onions were implicated, other types were also recalled because of possible contamination.

Potential Factors

Although the foodborne pathogen outbreak in onion is highly sporadic, efforts need to be made to understand the potential factors that affect bulb and root colonization of onion. Some of the potential factors may include a contaminated irrigation water source, use of non-pasteurized soil-amendments of biological origin, and preharvest and postharvest handling of onion.

An interdisciplinary team of research and Extension specialists at University of Georgia (UGA) has been working to understand the potential risk of contamination with food-borne pathogens in onion. The team has been focusing on understanding the ecology, biology, genetics and applied aspects of the onion-foodborne pathogen interface.

In particular, the team will evaluate if use of soil amendments like non-pasteurized or partially pasteurized poultry litter, cow manure or swine manure can be the source of salmonella contamination of the surface or ground waters in fields. Also, under controlled growth-chamber conditions, the risk of salmonella contamination in onion seedlings and onion bulbs through contaminated irrigation water will be evaluated. The team will also evaluate if there are any molecular signature(s) in the genome of salmonella that makes it potentially suitable to colonize onion.

Pathogen Persistence

A “trifecta approach” of considering ecology, biology and genetics can provide a long-term solution toward keeping onions free of foodborne pathogens. Sources of salmonella can include birds, reptiles and animals. Once shed in the environment, the pathogen can persist for several days to months in soil, irrigation water, sediment and animal/bird manure. Farming activities or changes in weather such as rainfall or dust storms can end up transferring salmonella to produce surfaces.

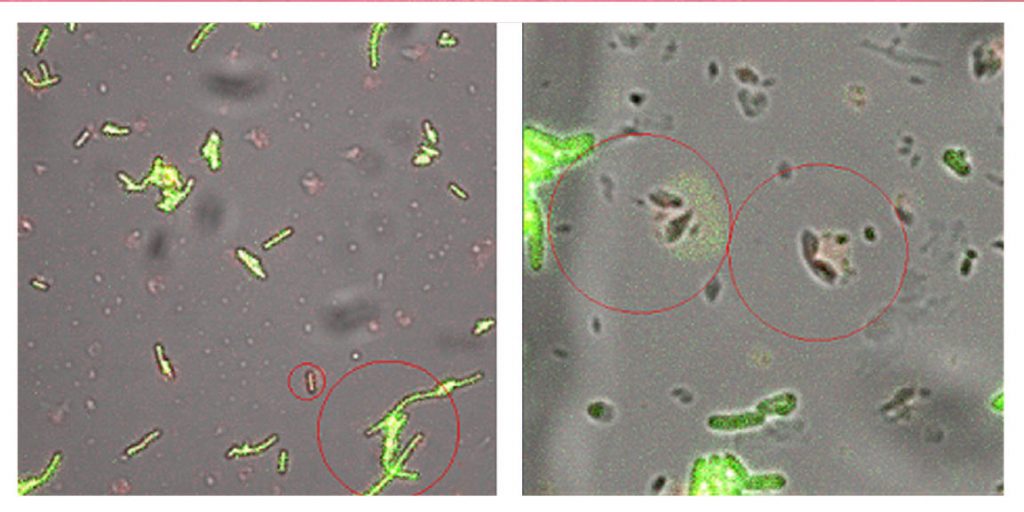

When present on seeds or transplants, salmonella has been known to not only remain on the surface, but also enter plant tissues (Figure 1). One of the mysteries being pursued by the UGA team is to understand if salmonella can survive in the presence of the antibiotic sulfur compounds released by onions. Salmonella strains may have acquired resistance genes to these natural sulfur antibiotics from closely related bacteria that commonly colonize onions. Studying how salmonella can adapt to an onion’s pungent environment will help unravel strategies used by the pathogen to survive on plants.

Studies will also assess the risks of salmonella dissemination from livestock waste into the environment through airborne and water distribution and the survival time of salmonella in onion. Researchers will study the relationship between the different types of salmonella present in nearby water bodies and those that will be isolated from onion. The information collected through these collaborative endeavors will help growers use practices that reduce the risk of contamination of onions by salmonella.

Bhabesh Dutta is an associate professor and vegetable Extension pathologist, Govindaraj Dev Kumaris an assistant professor, Brian Kvitkois an associate professor, and Hemant Naikareis an associate professor and director of the veterinary diagnostic lab — all at the University of Georgia.