Artificial intelligence (AI) may help Florida producers combat one of the most destructive pests farmers encounter every year.

University of Florida (UF) scientists are using AI to identify parasitic nematodes more rapidly. Some nematodes live in the ground and harm plants, while others are beneficial. It is important to distinguish which ones are which, said Peter DiGennaro, a UF/IFAS assistant professor of entomology and nematology.

DiGennaro and Alina Zare lead the research, which was among 20 projects to receive $50,000 last year through the UF Artificial Intelligence Research Catalyst Fund.

“We have the AI algorithms already developed but not for this issue,” Zare said. “We will need to apply them to the nematode imagery and further develop and validate the algorithm for this issue.”

Quicker Management Option

Growers need a quicker alternative in identifying nematodes in their soil to decide on the most efficient management treatment, DiGennaro said. Artificial intelligence could assist with this initial diagnosis of the nematode, making it quicker and cheaper to know what types of nematodes are in farmers’ fields.

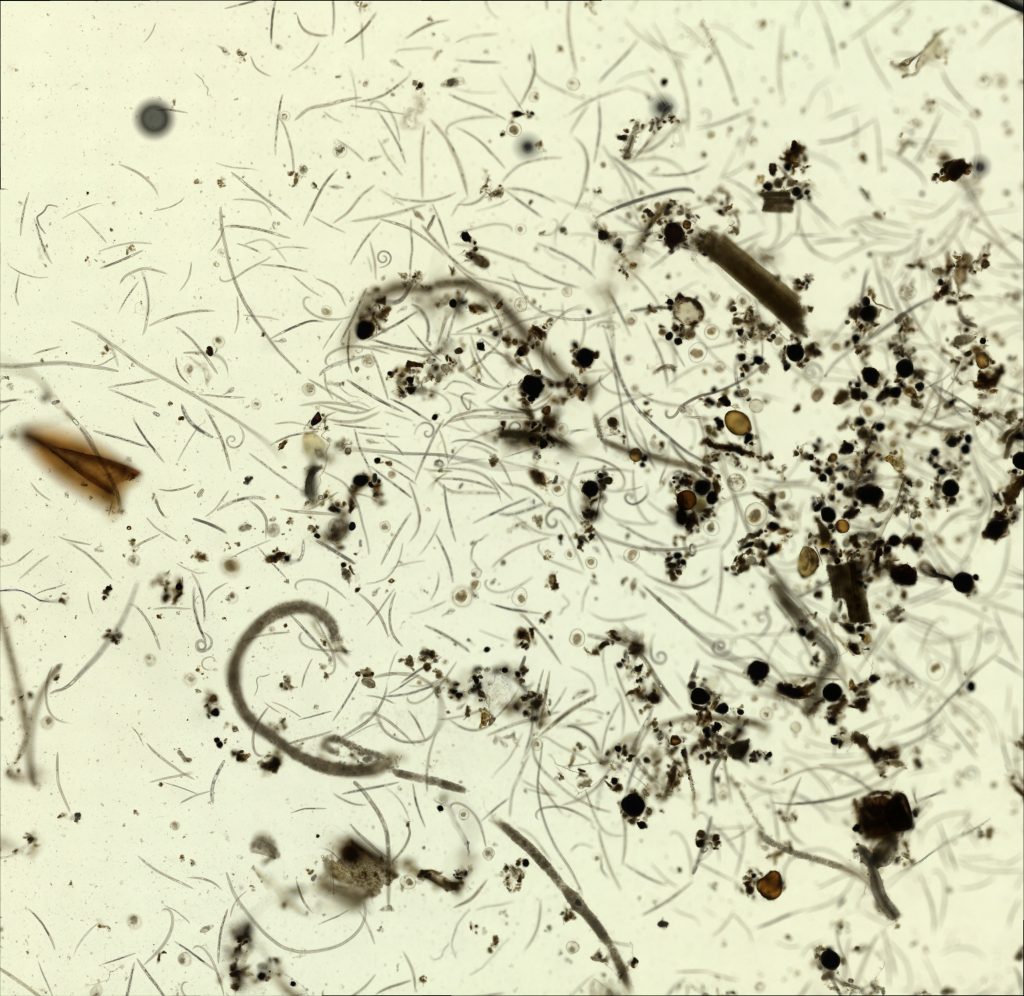

DiGennaro’s colleagues at the UF/IFAS Nematode Assay Lab receive about 7,000 samples each year from commercial growers, residents and golf courses in Florida. Lab specialists plan to view each sample with a digital microscope, which would capture about 15,000 images per sample, DiGennaro said. This can generate hundreds of thousands of images each year.

Time Consuming

This manual process is extremely time consuming. When the lab receives a soil sample, specialists extract the nematodes from the soil and view them under a microscope. They identify each kind of harmful nematode, count how many there are and assess the potential for plant damage.

With AI, the technology has the power to automate some of the processes, Zare said. DiGennaro and Zare are creating a machine-learning algorithm.

“Essentially, we pair each training image with a label,” said Zare, whose lab specializes in developing machine-learning algorithms that can learn from imprecise image-level labels, which are usually much easier, faster and cheaper to create than precise training labels. “Machine learning algorithms generally learn by repeatedly updating parameters until the output of the algorithm matches the desired outputs provided in the training labels.”

The algorithm will speed up the identification process of the nematodes. If the project succeeds, scientists could also tell growers which management practices would be most suitable to use to protect their crops.

“If artificial intelligence helps make nematode identification accurate and practical, it might reduce the lab’s labor costs and decrease turnaround time for nematode diagnosis,” said Billy Crow, UF/IFAS professor of nematology and director of the UF/IFAS Nematology Assay Lab. “The quicker we can tell a grower what is going on, the quicker they can do something about it.”